Tianle Chen

Ad exchanges sit between people who want to buy ads (advertisers) and those who wish to sell their ad spots (publishers). They help publishers maximize the value of each ad spot by collecting bids and ads from advertisers.

Online ad exchanges feel like stock exchanges. After all, they’re fast, automated, have huge daily volumes and have “exchanges” in their name.

Similarly, there are also large-cap “stocks” made up by prime internet properties such as YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter wherein one can find users who might be interested in something you’d like to sell. In the follow sections, we’ll look at a couple of features which make ad exchanges a uniquely different beast compared to stock exchanges.

What’s different?

Quantity has a quality of its own, and we can really see that in ad markets.

Ad opportunities are diverse

Here are some numbers to set a baseline for the size of a market:

- Nasdaq has about 2,500 stocks

- There are about 300 million companies in the world (120,000x Nasdaq)

- eBay has about 1 billion active listings (420,000x Nasdaq)

Now, how many ads are there in a day? We don’t have specific numbers but let’s try to think about the problem with a few key numbers:

- There are 400 million internet users in North America in 2022

- The average person in the US views over 100 page views in a day

- There’s about 10 ads on a page

Multiplying the above brings us to about 400 billion ads per day, easily dominating all the other markets we looked at above.

This quantity of ads is spread across the total number of active internet users (400 million) and the pages they viewed in a day (100), bringing us to about 10 ads per user, page pair. In comparison, Nasdaq had 33 million trades on 2023-11-09 over less than 2,500 stocks, which gives us 10,000 trades per stock. Thus, the number of trades to number of assets (stocks, or user-page pairs) for Nasdaq is 1000x that for online ads.

Nasdaq trades are a thousand times less diverse than that in ad markets.

They’re also cheap

On the other hand, advertising revenue in the US is $480 billion in 2022. This figure is reached in a single day on Nasdaq, where the trading volume for 2023-11-09 is already 240 billion USD.

| Daily Revenue | Daily Number of Trades | Revenue per Trade | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internet Ads | $1.3 billion | 400 billion | $0.003 (Multiply by 1000 to get a CPM of $3. But in reality CPMs can range between $0.30 and $3) |

| Nasdaq | $240 billion | 33 million | $7000 |

The amount of revenue per Nasdaq trade is 1 million times greater than that of an internet ad.

And vanish faster than the latest internet fad

Stock delistings are rare and usually makes the news but internet fads come and go every week. Ad opportunities vanish faster you can say “Mississippi” five times.

Pages need to load quickly to avoid losing users. Pages that take more than 5 seconds to load can lose more than 50% of users (source). Therefore, publishers are incentivized to minimize the time spent on loading ads (for revenue) to maximize the time allocated to generating content (for retention).

For real-time bidding, the response deadline is about 100ms (source), which is on the same scale of high-frequency stock trading. However, there’s generally no need to sell a stock within milliseconds (as is the case for ads) and sell orders can be active for days on the stock exchange.

Ads have to settle within milliseconds compared to hours or days for stocks.

TLDR

Compared to stock trades:

- Ad opportunities are 1,000x more diverse

- But brings in 1,000,000th of revenue

- And ads have to settle within milliseconds compared to hours or days.

What does it mean for the ad market?

It immediately follows from the above that pricing this many ads quickly and cheaply is not a easy problem to solve (humans need not apply). As such, the online ad industry has converged on the following solutions:

- Standardization of bid requests openrtb allow for algorithms to bid on important attributes related to web page, ad opportunity (on the page) as well as user information.

- Simple and fast automatic bidding algorithms (<100ms). Humans simply cannot react fast enough to the diversity of ad opportunities.

What do advertisers need to do?

The main character in Mad Men is a creative directive at an advertising agency whose job is to create advertisement campaigns. He appeals to the collective consciousness and leverages human desires to drive sales. It’s a story of intrigue, excitement and personal growth which makes for excellent TV.

These days, online advertisers still need to answer the same questions:

- What do I want to show to users? Do I want to show a video, static image or just text?

- What kind of users do I want? There are 5 billion internet users and even more internet-capable devices. Which ones are humans, and what do we know about them? Do I want to target by demographics or do I want to target a specific set of individual users (e.g. those who have visited my site before, have items in a cart)?

- Where do I want to show my ad? There are 1 billion websites in the world and even more if websites vary by user (e.g. Facebook or Instagram home feeds). Do I want to show the ad on the top, bottom, left or right side on a page?

On top of that, the modern internet advertising landscape has become a lot more metrics driven. Let’s look at a couple of metrics which measure the success of an advertising campaign.

- Cost Per Mille (Impressions) (CPM) The average amount spent per 1000 (i.e. mille) ads shown (i.e. impressions).

- Cost Per Click (CPC) The average amount spent per click on an ad. Usually the ad sends a user to a website upon clicking on it.

- Cost Per Lead (CPL) The average amount spent per “lead”. A “lead” can vary by advertiser but is usually associated with user actions that correlate highly with revenue (e.g. number of orders made by users after seeing an ad).

These core metrics all depends on the amount paid for an impression. This is therefore arguably the most important question:

How much should I pay for an ad?

Demand-side concerns

Basically there are three problems to solve on the demand-side:

- Creative generation (what does the ad look like?) This step has historically required the most manual involvement (e.g. via ad agencies). However, recent advances in Machine Learning has made it possible to automate parts of the ad generation process. Even more of it can be automated if the advertising platform is also a content platform where the thing you’re advertising already has some organic reach.

- Targeting (what does the ideal user look like?) Similar to the above, this can be automated if there’s already some engagement with users. Otherwise, this step would require human intuition and some skill in campaign management.

- Bidding (how much should I pay?) Often times, this is difficult for individual advertisers to influence directly. Typically, ad platforms have metrics driven offerings such as CPC (wherein advertisers are charged based on the number of clicks) or CPM (charging based on number of impressions) which incentivizes bidding to maximize the desired outcome.

Platforms typically take on the bidding risk

A platform charging by impressions or clicks typically take on the spread between the bidding logic and bidding outcomes. This means that even though their revenue depends on the bidding outcome (i.e. impressions or clicks), the ad platform cannot directly control the outcome. Therefore, if their bidding algorithms fail to deliver on the promised CPC or CPM metrics, they’ll take on the extra cost (and profit if they over deliver).

Ad platforms are therefore incentivized to optimize spend.

Bidding algorithms are usually very simple

Bids can be adjusted based on a variety of factors such as device type, time of day or whether a user is in a specific location (source). These influence the final bid value in a multiplicative way, as follows:

bid_value = starting_bid * adjustment_factor_A * adjustment_factor_B * ...

Typically, demand-side platforms (which advertisers interact with) run these algorithms and send bids to ad exchanges. Some even allow advertisers to modify these algorithms themselves.

The main advantages of this method are:

- Starting bids and individual adjustments can all be changed independently.

- The computation of the bid value can be distributed since the order of multiplication doesn’t matter.

- Extensions can be made for interaction effects, where the adjustments for a factor A may depend on the value of factor B. (i.e. by including

adjustment_factor_A_Bwherein the adjustment depends on values of both A and B).

However, there are limits to how this method can be extended. Typically, more sophisticated optimizations can be learned offline and fed into the bidding algorithms via lookup tables for the factors and their associated adjustments.

What about publishers?

Publishers’ concerns are mainly:

- Which ads can improve or not worsen user engagement? Therefore, publishers tend to have a fast scoring algorithm that decides whether an ad should be run on their property.

- How do I maximize revenue generated by ads? This is ensured by integrating with an optimal set of supply-side platforms and ad exchanges such that candidate ads score highly (see previous point) while maximizing bid values.

As far as I can tell, the ad market is not that interesting on the supply side since publishers’ strategies to optimize their outcome is generally aligned with their own reason for being - namely to produce interesting content that engages strongly with users on their platform.

The only interesting ad-related piece that publishers need to figure out is ad scoring.

That being said, this is just an optional piece since publishers always have the option to auction the ad slot to the highest bidder. Publishers may also offload the work to supply-side platforms.

What does an ad exchange do?

We now have the following pieces of an ad market from the demand and supply sides:

- Ad creatives The content of an ad.

- Ad targeting Where the ad should be shown.

- Bidding The amount advertisers are willing to pay for an ad to be shown on specific site to a specific set of users.

- Ad scoring The willingness of a publisher to display an ad (independent of ad bid).

The role of an ad exchange is therefore to put everything together and match advertisers with publishers. But how exactly does that happen?

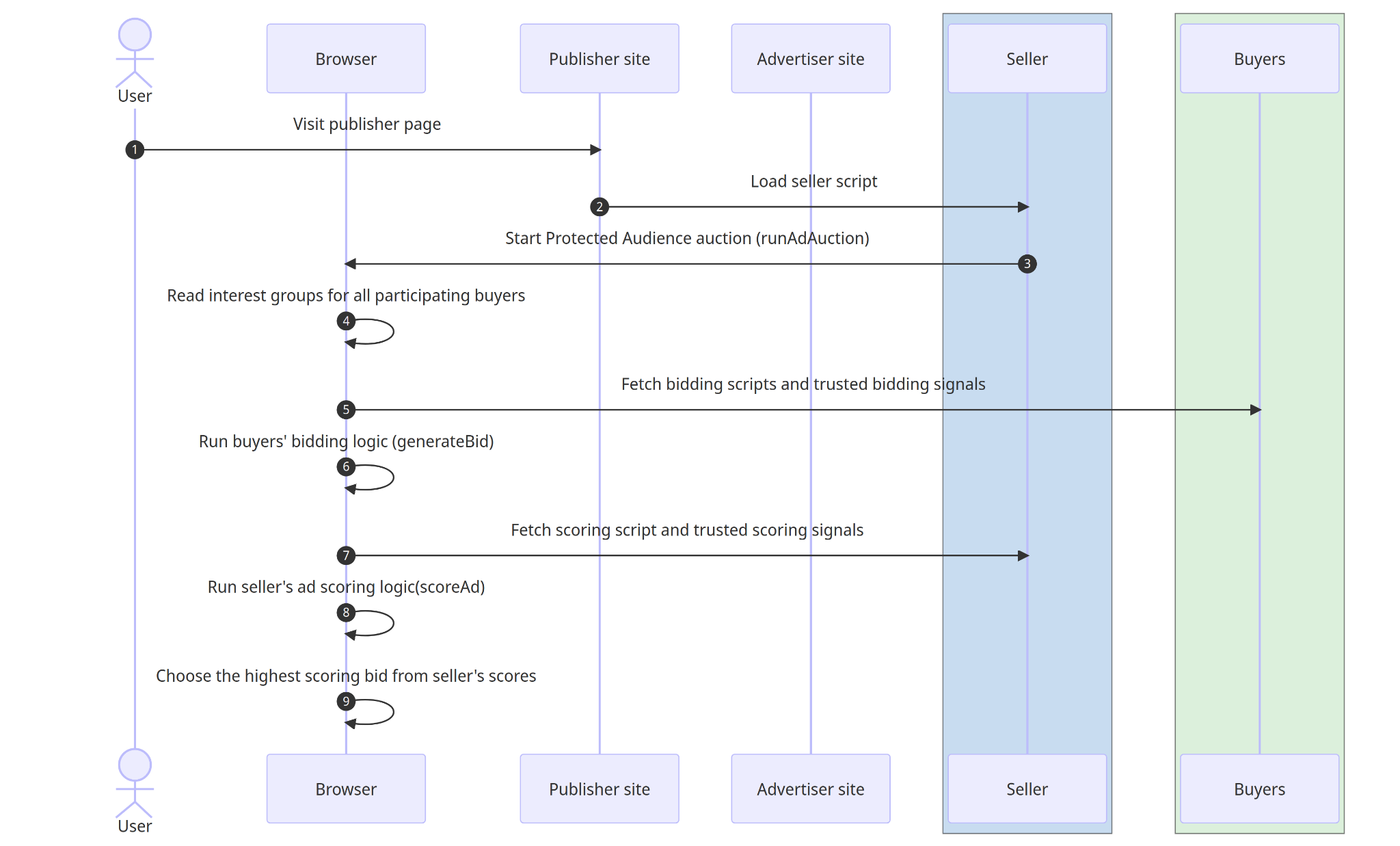

In the Protected Audience Webinar, the Chrome team describes a future in which auctions can be conducted without individually-identifiable information ever leaving the user’s browser. They also showed the steps required to connect Publishers (who host a website), Buyers (who help advertisers buy ads) and Sellers (who help publishers connect to buyers).

These steps in the middle of the sequence diagram are particularly insightful in describing the role of Publishers, Buyers, Sellers and Ad Exchanges in conducting an auction. Note that Ad Exchanges are not in the diagram because the Protected Audience API, but the diagram shows the roles in the current online advertising landscape.

| Step | Description | Currently done by |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | Find all participating buyers. | Ad exchanges |

| 5, 6 | Use bidding signals and bidding logic to generate bid value. | Buyers |

| 7, 8 | Use scoring signals and scoring logic to generate score. | Sellers |

| 9 | Choose the highest scoring bid from sellers’ scores, concluding the auction. | Ad Exchanges |

Finally, we should note that the role of an ad exchange is to make sure that all these steps are executed within a pre-determined amount of time (in milliseconds). This is done by optimizing the list of bidders and enforcing restrictions on the time taken for bidding and scoring algorithms.

- The number of buyers who may participate in the auctions is limited and so is the set of all possible ads that each buyer can produce bids for (source).

- Bid generation also needs to complete within 50-500 ms (source)

The plan now is to offload much of the Ad Exchange functionality to users’ Chrome browsers in the name of privacy. Maybe the users will be happy enough with the privacy aspect that they’ll ignore the fact that they’re literally running ad auctions to sell ads to themselves?

But that’s another topic for another day.